HttpSig is a simple but very efficient authentication protocol extending Signing HTTP Messages RFC by defining —

- a

WWW-Authenticate: HttpSigheader for servers to return to the client with a 401 or 402, - an

Authorization: HttpSigmethod the client can use in response with two optional attributeswebidandcert(todo) the first one takinghttpsURLs and the second takinghttpsorDIDURLs, - a requirement to interpret the

keyidattribute of theSignature-Inputheader defined in Signing HTTP Messages as a URI when used with theWWW-Authenticate: HttpSigheader, - the ability to use absolute or relative URLs in both paces mentioned above,

- allow relative URLs passed by the client to the server to refer to resources on the client using a P2P Extension to HTTP which would allow authentication over a single HTTP connection.

Signing HTTP Messages is an IETF RFC Draft worked on by the HTTP WG, whose purpose is to allow the signing of HTTP messages, be they requests or responses. Signing Messages is based on draft-cavage-http-signature-12, which evolved and gained adoption since 2013, and had a large number of implementations. The IETF spec does depart in important ways from the previous work, building on RFC 8941: Structured Header Fields and dropping the authentication feature which we are adding back here.

Signing Messages is a lightweight extension to the HTTP protocol. As such, it has full access to the HTTP layer. In comparison, TLS client authentication being established before the exchange of HTTP messages, does not have access to that layer. As a result, client certificate negotiation in TLS is constrained by the server only being able to list trusted Certificate Authorities.

Since HttpSig is an extension to Signing Messages it can directly access HTTP error codes, Link relation headers, and other metadata on a message. As a result, the client can use published access control policies to select among its credentials and use different identities on different requests. For example, a client can start by presenting an adult credential and later one for payment. If the client does not wish the server to link those properties, it would, of course, need to open a new connection.

(Note: all communication here is assumed to run over TLS.)

The Signing HTTP Messages protocol allows a client to authenticate by signing any of several HTTP headers with any one of its private keys.

To verify the signature, the server will needs to know the corresponding public key.

This information is passed in the form of an opaque string known as a keyid (see §2.4.2 Signature Parameters), which enable the server to look up the public key; how this look-up is done is not specified by that protocol.

The HttpSig protocol extension described here requires the keyid string to be interpreted as a URL.

This allows the server to discover the public key by resolving the keyid URL using standards defined for each URI scheme.

https URLs present the advantage of being widely used, but HttpSig is open to other schemes such as DIDs.

We first consider the minimal extension of Signing Messages with keyid's limited to HTTP urls.

We then show how this ties into the Access-Control Protocol used by Solid.

The minimal extension to Signing HTTP Messages can be illustrated by the following Sequence Diagram:

Client keyid Resource

App Document Server

| | |

|-(1) request URL -------------------------------------------------->|

|<-----------(1a) 40x + WWW-Authenticate: HttpSig + (Link) to ACR --|

| | |

| | |

|-(2) request Access Control Resource (ACR)------------------------->|

|<-------------------------------------(2a) 200 with ACR content ----|

| (choose key) | |

| | |

|-(3)- sign headers+keyid------------------------------------------->|

| | initial auth|

| | verification|

| | |

| |<-----------------(4) GET keyid----|

| |-(4a) return keyid doc------------>|

| - verify sig |

| - verify ACL |

| |

|<--------------------------------------------(3a) answer resource---|

Note that the core extension to "Signing HTTP Messages" occurs in exchange 2 and 3. 1 and 2 are just preparatory moves that set up the context.

In (1a) the Resource server answers a request (1), by sending a 401 or 402 response with the WWW-Authenticate: HttpSig header. The WWW-Authenticate header is specified in §4.1 of HTTP/1.1. The HttpSig challenge method needs to be defined here (todo) and registered as specified in the Authentication Scheme Registry.

We illustrate this with the following example. Alice makes a request to a resource </comments/> on her Personal Online Data Store (POD) at <https://alice.name>:

GET /comments/ HTTP/1.1

Accept: text/turtle, application/ld+json;q=0.9, */*;q=0.8The response from the server in (2) is the following:

HTTP/1.1 401 Unauthorized

WWW-Authenticate: HttpSig realm="/comments/"

Host: alice.name

Date: Thu, 01 Apr 2021 00:01:03 GMT

Link: <http://www.w3.org/ns/ldp#BasicContainer>; rel=type

Link: <http://www.w3.org/ns/ldp#Resource>; rel=type

Link: </comments/.acl>; rel=aclThe Link header with a rel value of acl works as described in the Web Access Control Spec.

It is what allows clients making a request on a resource to find out what credentials they need to gain the access they were denied.

Without such a Link the client would only be able to guess what key to send,

leading to the following dilemma: either the client loses privacy by randomly having to present its credentials, allowing the server to correlate those identities, or the client has to resign itself to not accessing resources it is actually entitled to. Presenting the access rules avoids clients having to choose between such unappealing extremes.

We illustrate a client discovering this information in request 2 and answer 2a.

Note: With HTTP/2 server Push, the server could immediately push the content of the linked-to Access Control document to the client, assuming reasonably that the client would have connected with the key had it known the rules. It may also be possible to send the relevant ACL rules directly in the body of the response (see discussion on issue 167).

The Access Control rule could be as simple as stating that access will be granted only to requests authenticate using one of a set of keys. More complicated use cases are possible, as described in the Use Cases and Requirements Document.

If the client can find a key that satisfies the Access Control Rules, then it can use the corresponding private key to sign the headers in (3) as specified by Signing HTTP Messages and pass a link to the key in the keyid field as a URL.

Assume that Alice's client, after parsing the Access Control Rules found that https://alice.name/keys/alice# satisfies the stated requirements. If Alice allows the client to use that key, the app can create a signing string for the @request-target pseudo-header and authorization header. The authorization header is mandatory to avoid a man in the middle attack (is it really?) that could change the Authorization header to point to a different signature.

First Alice's client builds a pre-signed request, containing an Authorization header as shown here:

GET /comments/ HTTP/1.1

Authorization: HttpSig proof=sig1

Accept: text/turtle, application/ld+json;q=0.9, */*;q=0.8This request is used to generate a signing string on the @request-target and authorization headers:

"@request-target": get /comments/

"authorization": HttpSig proof=sig1

"@signature-params": ("@request-target" "authorization");keyid="/keys/alice#";\

created=1617265800;expires=1617320700

After signing the above string with the private key of </keys/alice#> and naming that signature sig1, the new HTTP request header looks as follows:

GET /comments/ HTTP/1.1

Authorization: HttpSig proof=sig1

Accept: text/turtle, application/ld+json;q=0.9, */*;q=0.8

Signature-Input: sig1=("@request-target" "authorization");keyid="/keys/alice#";\

created=1617265800;expires=1617320700

Signature: sig1=:jnwCuSDVKd8royZnKgm0GBQzLcad4ynATDIrkNkQGHGY6Dd0ftc0MKX88fZwek\

KevNW4N5eky+idEqOsvj+wpxc7xXN7KwnAT0SzGjyj+3CxnVN26er72l1zWDRBxo7IN3raKi0wE\

Oxv7mW2Ms9/VQ4gChyTK+n2zUz+nuly/6cKlJDwqsbb6MDFq88p6OYjx3AFwqlgJvQ5U1RCkZzI\

1X6P98pE0oY8Z8xu5dtyCwVBVyLXkAdeVlCABA3jdZB/qorSmbEgoQBXVvLsNaVAkAnIGY6sEFv\

j0FZ/90URJSeraJLrHmOhOIwL5T11mIdhmlqLCk4werRFfbfRBTBQ9g==:Notes:

- we have encoded the header using RFC8792 Single Slash Encoding to fit the longer lines on a page,

- the public and private keys are the same as those named

test-key-rsa-pssgiven in Appendix B.1.2 of Message Signatures, - the HttpSig Authorization message interprets any

keyidto be a relative or absolute URI, - in the example above, the

keyidis a relative URL pointing to a resource on Alice's POD.

The main protocol extension from Signing HTTP Messages RFC is that of requiring the keyid to be a URL, allowing the resource server to retrieve the keyid document in (4).

In our example, the Resource Guard on the POD alice.name retrieves the resource </keys/alice> receiving the following JSON-LD 1.1 document:

{

"@context": [

"https://w3id.org/security/v1",

{ "ex": "http://example.org/vocab#" }

],

"id": "#",

"controller": "/people/alice#i",

"publicKeyJwk": { "kty":"RSA",

"e":"AQAB",

"n":"hAKYdtoeoy8zcAcR874L8cnZxKzAGwd7v36APp7Pv6Q2jdsPBRrwWEBnez6d0UDKDwGbc6nxfEXAy5mbhgajzrw3MOEt8uA5txSKobBpKDeBLOsdJKFqMGmXCQvEG7YemcxDTRPxAleIAgYYRjTSd_QBwVW9OwNFhekro3RtlinV0a75jfZgkne_YiktSvLG34lw2zqXBDTC5NHROUqGTlML4PlNZS5Ri2U4aCNx2rUPRcKIlE0PuKxI4T-HIaFpv8-rdV6eUgOrB2xeI1dSFFn_nnv5OoZJEIB-VmuKn3DCUcCZSFlQPSXSfBDiUGhwOw76WuSSsf1D4b_vLoJ10w",

"alg":"PS512",

"kid":"2021-04-01-laptop"

}

}The server could also return an equivalent Turtle 1.1 representation:

@prefix security: <https://w3id.org/security#> .

</keys/alice#>

security:controller </people/alice#i> ;

security:publicKeyJwk """{

"alg":"PS512",

"e":"AQAB",

"kid":"2021-04-01-laptop",

"kty":"RSA",

"n":hAKYdtoeoy8zcAcR874L8cnZxKzAGwd7v36APp7Pv6Q2jdsPBRrwWEBnez6d0UDKDwGbc6nxfEXAy5mbhgajzrw3MOEt8uA5txSKobBpKDeBLOsdJKFqMGmXCQvEG7YemcxDTRPxAleIAgYYRjTSd_QBwVW9OwNFhekro3RtlinV0a75jfZgkne_YiktSvLG34lw2zqXBDTC5NHROUqGTlML4PlNZS5Ri2U4aCNx2rUPRcKIlE0PuKxI4T-HIaFpv8-rdV6eUgOrB2xeI1dSFFn_nnv5OoZJEIB-VmuKn3DCUcCZSFlQPSXSfBDiUGhwOw76WuSSsf1D4b_vLoJ10w"

}"""^^rdfs:JSON .(See issue 156: Ontology for keyid document)

Since the keyid URL, in our example, is relative, the server will not need to make a new network connection to the outside world.

Indeed, here is a list of contexts in which a connection to the internet will not be necessary:

- The

keyidURL points to a resource on the resource server. - The

keyidURL is a did:key or did:jwt URL (see issue 157). These are URIs that contains in their name all the data of the public key. Since the signing string always contains the@signature-paramsfield, this data cannot be altered. - The

keyidURL refers to an external resource, but the resource server has a fresh cached copy of it, or the URL refers to adid:...document stored on some form of blockchain, which the server has access to offline. - The

keyidis a relative URL on the client, which the server can GET using the P2P extension to HTTP (more on that below).

One advantage of using https URLs to refer to keys, is that they allow the client to use HTTP Methods such as POST or PUT to create keys, as well as PUT, PATCH and DELETE to edit them, helping address the problem of key revocation.

Whichever keyid scheme is used, the Resource's Guard will be able to check the linked-to Web Access Control Rules, and so discover if access can be granted to a user identified with that key (see The Access Control Rules below).

The Solid Use Case will help us justify why we need identifiers whose visibility is not necessarily tied to just one resource server. We start by noticing that Solid (Social Linked Data) clients are modeled on web browsers. Solid clients are not tied to reading or writing data from one domain; just like web browsers, they can start from a resource located on any server and follow links from there to arrive anywhere else on the web. As a result, Solid Apps cannot know in advance of making a request on a resource, whether authentication will be needed or what credentials will need to be presented.

Furthermore, many Solid App users will be keen to create cross-site identities and link them up, in order to join decentralized conversations and build reputations across websites.

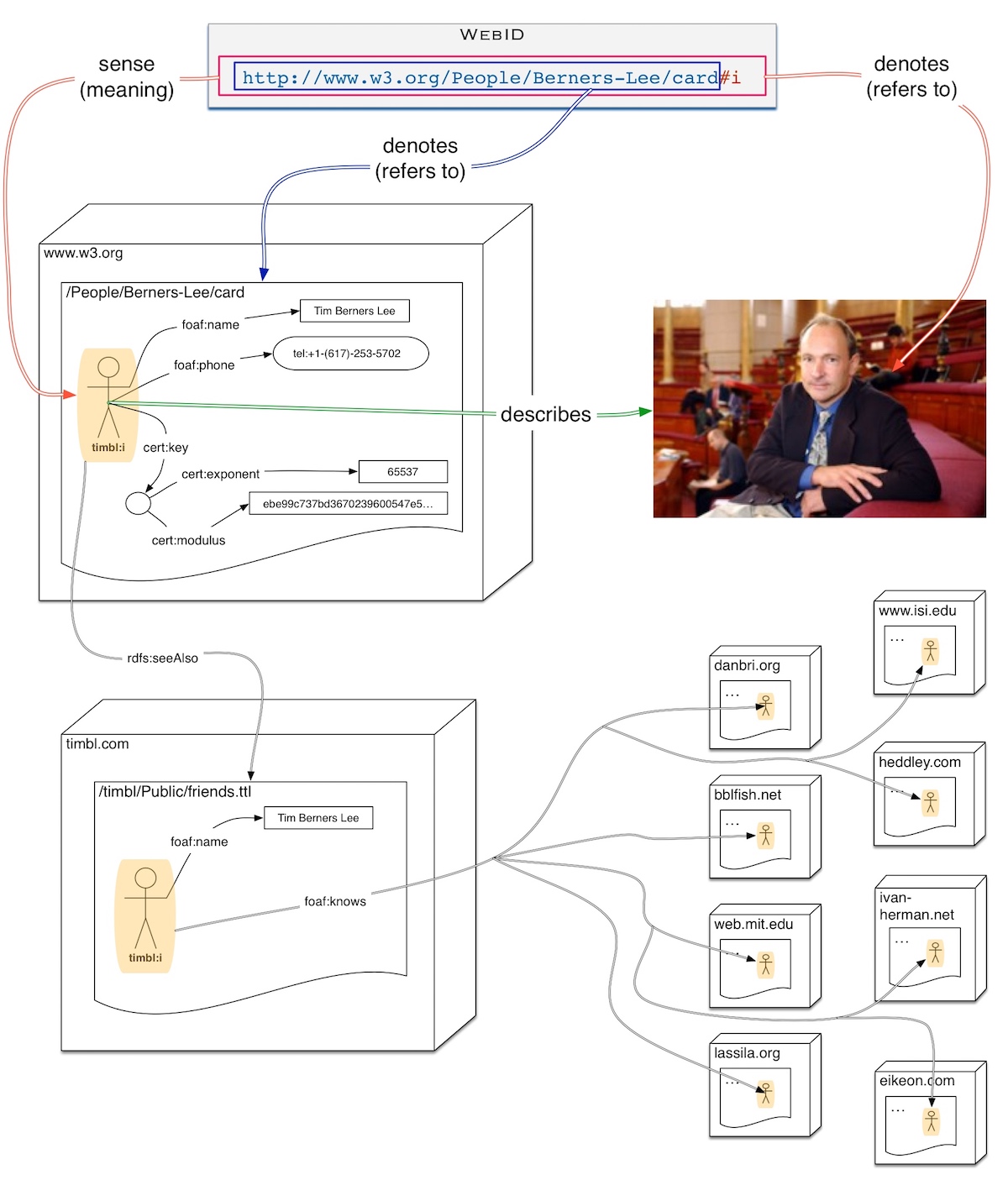

We can illustrate this by the following diagram showing the topology of the data a solid client may need to read. Starting from Tim Berners-Lee's WebID, a client may need to follow the links spanning web servers (represented as boxes).

Starting from one resource, such as TimBL's WebID, a client should be able to follow links to other resources, some of which will be protected in various ways, requiring different forms of proof.

When used with HttpSig all keyid parameters are to be interpreted as URLs.

To take an example from §A.3.2.1 of the Message Signing RFC, this would allow the following use of relative URLs referring to a resource on the requested server

Authorization: HttpSig proof=sig2

Signature-Input: sig2=(); keyid="/keys/test-key-a"; created=1402170695

Signature: sig2=:cxieW5ZKV9R9A70+Ua1A/1FCvVayuE6Z77wDGNVFSiluSzR9TYFV

vwUjeU6CTYUdbOByGMCee5q1eWWUOM8BIH04Si6VndEHjQVdHqshAtNJk2Quzs6WC

2DkV0vysOhBSvFZuLZvtCmXRQfYGTGhZqGwq/AAmFbt5WNLQtDrEe0ErveEKBfaz+

IJ35zhaj+dun71YZ82b/CRfO6fSSt8VXeJuvdqUuVPWqjgJD4n9mgZpZFGBaDdPiw

pfbVZHzcHrumFJeFHWXH64a+c5GN+TWlP8NPg2zFdEc/joMymBiRelq236WGm5VvV

9a22RW2/yLmaU/uwf9v40yGR/I1NRA==:But it would also allow for absolute URLs referring to keyid documents

located elsewhere on the web, such as the requestor's Freedom Box:

Signature-Input: sig1=(); keyid="https://alice.freedombox/keys/test-key-a"; created=1402170695

Signature: sig1=:cxieW5ZKV9R9A70+Ua1A/1FCvVayuE6Z77wDGNVFSiluSz...==:It also allows key-based DID URLs as described in issue 217 of the Solid Spec.

In order to allow relative URLs to refer to resources on the client, as made possible by the Peer-to-Peer Extension to HTTP/2 draft (see discussed on the ietf-http-wg mailing list) the Authorization header can be enhanced with a clientUrl parameter.

Here is an example of a header sent by a client to the server with such a URL:

Authorization: HttpSig proof=sig3, clientUrl=true

Signature-Input: sig3=(); keyid="/keys/test-key-a"; created=1402170695

Signature: sig3=:cxieW5ZKV9R9A70+Ua1A/1FCvVayuE6Z77wDGNVFSiluSzR9TYFVOn receiving such a signed header, the server would know that it can request the key by making an HTTP GET request on the given relative URL on the client using the same connection but after switching client/server roles.

This would reduce to a minimum the reliance on the network.

The keyid is a URL that refers to a key.

An example key would be:

https://bob.example/keys/2019-09-02#k1

The URL without the hash refers to the keyid document,

which can be dereferenced. In the above example, the keyid document is

https://bob.example/keys/2019-09-02.

For the Solid use cases, the keyid document must contain a description of the public key in an RDF format.

Following discussion in issue 156: Ontology for keyid document and in order to maximise interoperability with the Web Credentials community, the document has to use the security-vocab.

The server must present both Turtle and JSON-LD formats. This format embeds a JSON Literal for the key as specified by RFC 7517: JSON Web Key (JWK) into the RDF. An example keyid document was given with Alice's keyid document above.

How can the client know which key to present? We illustrate this with a few examples building on Solid Web Access Control.

In the simplest case, a Web Access Control rule document linked to from the Link: header of the resource the client received a 401 from, can specify a set of agents by describing their relation to a public key.

@prefix acl: <http://www.w3.org/ns/auth/acl#>.

@prefix cert: <http://www.w3.org/ns/auth/cert#> .

<#authorization1>

a acl:Authorization;

acl:accessTo <https://alice.example/docs/shared-file1>;

acl:mode acl:Read,

acl:Write;

acl:agent [ cert:key </2019-09-02#k1> ],

<did:key:z6MkiTBz1ymuepAQ4HEHYSF1H8quG5GLVVQR3djdX3mDooWp>,

[ cert:key <https://iama.star/love/me/key#i> ] .Instead of listing agents individually in the ACL, they can be listed as belonging to a group

<#authorization1>

a acl:Authorization;

acl:accessTo <https://alice.example/docs/shared-file1>;

acl:mode acl:Read,

acl:Write,

acl:Control;

acl:agentGroup <https://alice.example.com/work-groups#Accounting> .The agent Group document located at https://alice.example.com/work-groups can describe the users in various ways including by keyid as in this example

<#Accounting>

a vcard:Group;

# Accounting group members:

vcard:hasMember [ cert:key </keys/2019-09-02#k1> ],

[ cert:key <https://iama.star/love/me/key#i> ],

<did:key:z6MkiTBz1ymuepAQ4HEHYSF1H8quG5GLVVQR3djdX3mDooWp> .The Group resource can itself be access controlled to be only visible to members of the Group.

We now look at how the protocol can be extended beyond possession of a key to proving attributes based on a Credential.

A Credential is a document describing certain properties of an agent. It can be a WebID or a Verifiable Credential. We can refer to such a document using a URL.

If the Access Control Rule linked to in (2) specifies that only agents that can prove a certain property can access the resource, and the agent has such credentials in its Universal Wallet, the agent can choose the right credentials depending on the user's policies on privacy or security. If the policies do not give a clear answer, the user agent will need to ask the user -- at that time or later, but in any case before engaging in the request (3) - to confirm authenticated access.

Having selected a Credential, this can be passed in the response in (3) to the server by adding a Authorization: HttpSig header with as cred attribute value a relative or absolute URL enclosed in < and > referring to that credential.

GET /comments/c1 HTTP/1.1

Authorization: HttpSig proof=sig1, cred="<https://alice.freedom/cred/BAEng>"

Signature-Input: sig1=(); keyid="<https://alice.freedom/keys/alice-key-eng>"; created=1402170695

Signature: sig1=:cxieW5ZKV9R9A70+Ua1A/1FCvVayuE6Z77wDGNVFSiluSzR9TYFV

vwUjeU6CTYUdbOByGMCee5q1eWWUOM8BIH04Si6VndEHjQVdHqshAtNJk2Quzs6WC

2DkV0vysOhBSvFZuLZvtCmXRQfYGTGhZqGwq/AAmFbt5WNLQtDrEe0ErveEKBfaz+

IJ35zhaj+dun71YZ82b/CRfO6fSSt8VXeJuvdqUuVPWqjgJD4n9mgZpZFGBaDdPiw

pfbVZHzcHrumFJeFHWXH64a+c5GN+TWlP8NPg2zFdEc/joMymBiRelq236WGm5VvV

9a22RW2/yLmaU/uwf9v40yGR/I1NRA==:As before, we reserve the option to enclose a relative URL in > and < to refer to a client side resource, accessible by the server using a P2P extension of HTTP (see Peer-to-Peer Extension to HTTP/2 draft).

(Todo: how else can one pass the Credential?).

Client Resource keyid Credential

App Server Doc Doc

| | | |

|-(1) request URL --------------------->| | |

|<-------------(2) 401 + WWW-Auth Sig | | |

| + Link acl header --| | |

| | | |

|-(2) request ACR --------------------->| | |

|<-------------------(2a) 200 ACR doc --| | |

| | | |

| (select cert and key) | | |

| | | |

|-(3) HTTP Sig header------------------>| | |

| initial auth | | |

| verification | | |

| | | |

| |-(4) GET keyid--------->| |

| |<--------(4a) keyid doc-| |

| | |

| verify sig | |

| | |

| |-(5) GET credential---------------->|

| |<---------------(5a) credential Doc-|

| |

| WAC verification |

| |

|<-----------------(3a) send content----|

Exchange 4, where the server retrieves a (cached) copy of the key, are as before.

Exchange 5 to fetch the Credential document can run in parallel with 4.

And the result sent in 5a can also can be cached.

If the Credential header URL

- is enclosed in '<' and '>' then

- if it is relative it can be fetched on the same server

- if is is an absolute URL it can be fetched by opening a new connection

- is enclosed in

>and<and P2P HTTP extension is enabled, the server can request the credential from the client directly using the same connection opened in (3) exactly as above.

Note that if a client uses a P2P Connection to fetch a >/cred1< Credential and the client is authenticated with a did:key:23dfs then the server may be able to store that Credential at the did:key:23dfs/cred1 URL in its cache. (todo: think it through)

We start by illustrating this with a very simple example: that of authentication by WebID.

Here we consider a WebID Document profile document to be a minimal credential - minimal in so far as it does not even need to be signed.

The signature comes from the TLS handshake required to fetch an https signed document placed at the location of the URL.

The simplest deployment is for the WebID document to be the same as the keyid document.

For example Alice's WebID and keyid documents

could be https://alice.example/card and return

a representation with the following triples:

<#me> a foaf:Person;

foaf:name "Alice";

cert:key <#key1> .

<#key1> a cert:RSAPublicKey;

cert:modulus "00cb25da76..."^^xsd:hexBinary;

cert:exponent 65537 .By signing the HTTP header with the private key corresponding to the public key published at <https://alice.example/card#key1> the client proves that it is the referrent of <https://alice.example/card#me> according to the description of the WebID Profile Document.

This can be used for people or institutions that are happy to have public global identifiers to identify them.

One advantage is that the keyid document being the same as the WebID Profile document, the verification step requests (4) and (5) get collapsed into one request.

It also allows each individual user to maintain their profile and keys by hosting it on their server.

This allows friends to link to it, creating a friend of a friend decentralized social network.

A certain amount of anonymity can be regained by placing those servers behind Tor, using .onion URLs, and access controlling linked to documents that contain more personal information.

WebIDs allow servers to protect resources by listing WebIDs as shown in the Groups of Agents description of the Web Access Control Spec. Because the keys are controlled by the users, they can update them regularly, especially if they suspect a private key may have been compromised.

Authors of such ACLs can evaluate the trust they put in such a WebID by the position it has in their Web of Trust (i.e. which other people they trust link to it).

Access Control Lists can be extended by rules giving access to friends of a friend, extended family networks, ... (this is still being worked on)

WebIDs are also useful for institutions wishing to be clearly identified when signing a Verifiable Credential, such as a Birth Certificate or Drivers License Authority signing a claim, a University or School signing that a user has received a degree, ...

When WebID and keyid documents are different this allows the key to be used without tying it to a WebID, and for that key to be used to sign other credentials.

It can also be useful in that the container where keys are placed can have less strict access control rules that the WebID profile, giving various software agents access to them.

In this case the WebID could link to the hash of the key, or some other proof that does not require it linking to the key.

Resources can describe in the linked-to accessControl document a class of agents, specified by attribute, who may access the resource in a given mode.

For example, ISO could publish an OWL document at https://iso.org/ont/People, describing the set of people over 21, using an example from the OWL2-Primer.

<#Over21> owl:equivalentClass [ a owl:Restriction;

owl:onProperty :hasAge ;

owl:someValuesFrom

[ rdf:type rdfs:Datatype ;

owl:onDatatype xsd:integer ;

owl:withRestrictions ( [ xsd:minExclusive 21 ] )

]

] .This would allow resources to be protected with a rule such as

<#adultPermission>

:accessToClass :AdultContent;

:agentClass iso:Over21 ;

:mode :Read .After receiving the response (2) in the above sequence diagram, a client can search for the relevant Verifiable Credential in its Universal Wallet (containing perhaps a Drivers License, Birth certificate, and MI7 007 license to kill), order these in a privacy lattice, and choose the one most appropriate for the task at hand. The URL for that Credential can then be sent in the header (3).

Here is an example that would work over an HTTP/2 connection enabled with a P2P extension. The client tells the server to find the certificate in its local store at /certs/YearOfBirth. The server could then resolve that relative URL to <did:key:z6MkiTBz1ymuepAQ4HEHYSF1H8quG5GLVVQR3djdX3mDooWp/certs/YearOfBirth> and check its cache for a valid cert. If none is present, it would need to request one from the client on the same P2P connection at /certs/YearOfBirth/.

GET /comments/c1 HTTP/2

Authorization: HttpSig cred=">/certs/YearOfBirth<" .

Signature-Input: sig1=(); keyid="did:key:z6MkiTBz1ymuepAQ4HEHYSF1H8quG5GLVVQR3djdX3mDooWp"; created=1402170695The Server Guard then needs to verify that the signature is correct, that the credential identifies the user with the same key, and that it is signed by a legitimate Certificate Authority entitled to make Claims about age.

How to determine which Certificate Authority are legitimate for which claims, is outside the scope of this specification. This is known in the Self-Sovereign Identity space as a Governance Framework, and will potentially require a Web of Nations.